Author: Daniel J. Schaeffler, Ph.D.

First published in the February 2018 issue of MetalForming Magazine

“I need some cold-rolled for this part!” “Get me some 1008/ 1010!”

You might think that you know what you’re asking for, but when talking with your supplier, it’s important that you both use the same language to be sure you’ll get what you need.

Sheetmetal

Sheetmetal

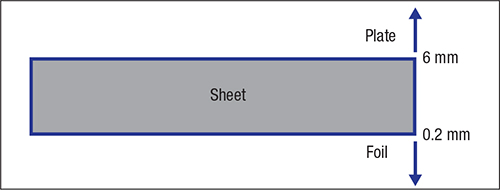

Sheetmetal is simply any metal alloy that stores as a sheet, or is coiled as a matter of convenience to ease handling–some coils stretch for more than a mile. Although no firm break exists between categories, for most alloys, sheet thickness ranges from 0.2mm to 6mm (0.008 inch to 0.25 inch). Plate refers to thicker material, while foil denotes thinner. Some use the term ‘shate’ for aluminum from 4 to 6 mm, too thin to be called plate.

The term sheetmetal only describes thickness, and does not inform as to width, chemistry or tensile properties. Coils produced at sheet steel mills typically measure 1000 to 2000 mm (40 to 80 inches) wide, with some aluminum mills capable of producing wider sheets. Rolling the thinnest-widest combination while maintaining tight tolerances on both is challenging for most production mills. This is one reason not all products are available at every thickness or width. A strip mill maintains tight thickness tolerances at relatively narrow coil widths, usually less than 600 mm (24 inches).

Understanding Heat Sizes, Continuous Casting, and Ingot Casting

Whether steel or aluminum, all coils start off as one batch of liquid metal, with each batch referred to as a heat. Heat sizes at steel mills can measure to 300 tons, while those at some aluminum mills approach 50 tons. Each heat has a uniform composition, so the chemistry reported on all products from the same heat will be identical. This usually is the chemistry measurement that appears in a listing of certified metal properties.

All steel and some aluminum mills convert liquid metal into a solid form via continuous casting, with the discrete solid units referred to as slabs. One heat can produce 10 or more cast slabs. Most aluminum mills, as well as mills working with other metals and alloys, cast liquid into individual units called ingots. Sometimes alloying elements segregate during solidification, especially during ingot casting. This may lead to a variation in chemistry in different locations, such as at the surface as compared with the center. However, the bulk chemistry remains the same as when the material was liquid.

Rolling and Pickling of Sheetmetal Coils

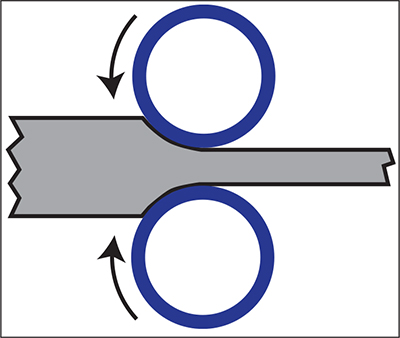

Rolling comprises the next major processing step in the conversion of a slab or ingot to coiled sheet (Fig. 2). Here, thickness is reduced in a way similar to the use of rolling pins for flattening dough. Sheetmetal requires more rolling force than bread, so initial rolling occurs at a high temperature, hence the term hot rolling. Elevated temperatures deliver an easier way to make larger thickness reductions in succeeding passes. Because width does not change, the metal band elongates with every thickness reduction, while also increasing speed through the rolling mill. Most sheetmetal grades slow-cool in coil form, while faster cooling rates change the microstructure to increase strength. For at least some grades, hot-rolled alloys can carry the same strength and ductility as cold-rolled grades, but usually with different property ranges, wider dimensional tolerances and rougher surfaces.

Steel surfaces oxidize and create scale, a form of iron oxide that must be removed before further processing—performed by passing the material through acid in a pickling step. Rust-preventive oil added to the surface, if this is the desired end product, leads to the term “hot-rolled, pickled and oiled,” or HRPO. Some hot-rolled steels measure as thin as 1.5 mm, with 3-5 mm typical for most production mills. Should thinner material or additional processing be required to develop desired properties. The steel hot band is sent for cold rolling. Limited industrial applications exist for stamped aluminum sheet after hot rolling. This makes the process primarily an intermediate step prior to cold rolling.

As the name indicates, cold rolling occurs at ambient temperatures. Thickness reductions of 70 to 90 percent creates targeted properties of the ordered material. This rolling step increases material strength to the full-hard condition, but the material is now too brittle for a select few applications. Annealing, or heating the coil above a critical temperature, relieves internal stresses in the sheetmetal. Changing how the steel or aluminum cools from the annealing temperature affect its tensile properties. Calling something “cold-rolled” only reveals some of the processing performed on a coil. It doesn’t narrow down the hundreds of grades at steel or aluminum mills.

Melt chemistry, rolling practice, annealing cycle as well as other processing steps such as coating or leveling all affect the forming and joining properties of sheetmetal grades. Be sure to use terms that your material supplier understands. Otherwise, you might not get what you want…or what you need.